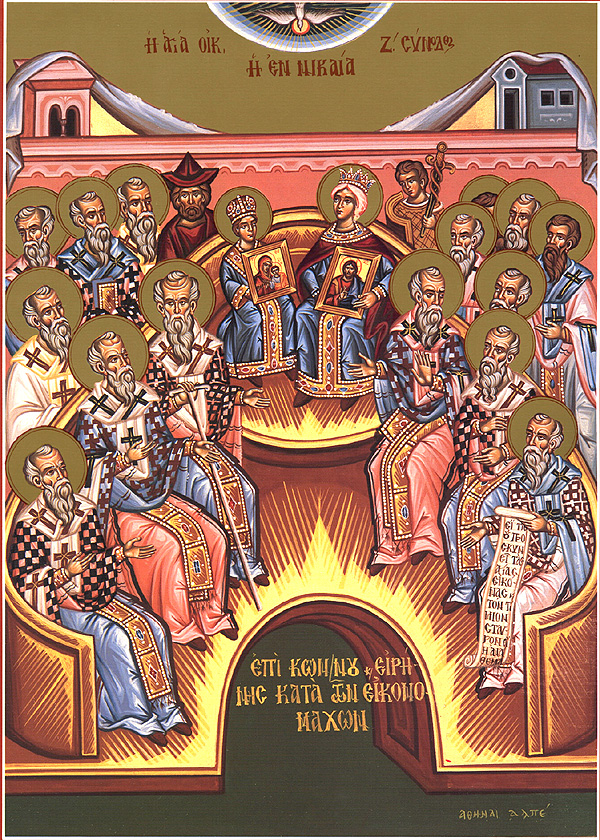

Sermon: Sunday of the 7th Ecumenical Council

4th Sunday of Luke

Sunday of the Holy Fathers of the 7th Ecumenical Council

Titus 3:8-15, Luke 8:5-15

Today’s parable about the Sower calls us to consider what we have done with the faith we have received as Orthodox Christians. It also provides us with an opportunity to say a few things about this faith, especially since today is also the Sunday of the seventh Ecumenical Council, which defended the Orthodox theology of the holy icons.

The question of iconography was not a question of liturgical art, but of Christology — the question of who we believe Jesus Christ to be. All of the various christological dogmas expressed at the first six councils, are summarised in the seventh, and are expressed through the visual depiction of our Lord Jesus Christ.

The first issue dealt with by the Ecumenical Councils was the relationship of God the Son with the Father. Not whether Christ was God — all Christians, including the heretics, believed in Christ’s divinity — but rather in what way Christ is God. The heretic Arius maintained that the Son was begotten from the Father in time. In other words, first there was God, and at a later point in time the Son appears, and God then creates the world through him. The Son, therefore, was some kind of secondary deity, and not equal to the Father.

To this heresy, the Church replied as follows: First of all, if the Son, who is the Wisdom and Word of God, was not there from eternity, this means God was imperfect before they came into being. And if the Son did not always exist, this means that God was not always the Father — it means that God changed, even though the Scriptures say clearly that with God “there is no change nor shadow cast by turning” (James 1:17). Furthermore, if the Son does not share the same divinity as the Father, if he is something separate from God, how can he be worshipped? “Hear, O Israel, the Lord thy God, the Lord is one”. Only one God is worthy of worship; there can be no other.

For this reason, the fathers of the First Ecumenical council proclaimed that “We believe in one God”, and that his Son and Word is “of one essence with the Father” and that he was “begotten from the Father before all ages”. In other words, there was never a moment when God the father did not have with him his Word and his Spirit. Just like it is proper to the nature of a flame to issue forth heat and light, so the begetting of the Son and the procession of the Spirit are proper to God the Father. We can distinguish between the three persons of the Holy Trinity, but never separate them. The Triune God is one God, with one nature, one essence, one will, one energy, and is worshipped with one worship.

The second question facing the Ecumenical Councils was the Incarnation of the Lord — in other words, what do we mean when we say that God became a man in the person of Jesus Christ?

The basic teaching of the Church is very simple. Man had been separated from God, and God therefore became man in order to bridge that gap, in order to unite the Creator and the creation. After all, that is what salvation means: it means union with God. Therefore, in order for salvation to be possible, there has to be in Christ a true union of the divine nature with the human nature; but at the same time, these two natures have to remain intact and unchanged.

The Monophysite heresy held that the two natures of Christ joined to form one theanthropic, divine-human, nature. But this is mixture, not union. And it means that Christ is neither fully divine, nor fully human. He doesn’t fully belong to either side, and therefore there is no union, and so no salvation. Other heresies suggested that Christ had no human soul, no human will and energy, which again means that Christ would not be fully man.

The opposite heresy was that of Nestorius, who didn’t accept the true union of the natures. This is why he didn’t accept the term Theotokos (Birthgiver of God) with reference to the Virgin Mary, since she was only the mother of his human nature, not of his divinity.

Here, the Church replied that, it is not abstract natures which are born, which act and speak, but rather Persons (hypostases). Nestorius was right to say that Christ only took his human nature from the Virgin Mary, but it was God, the Person of God the Word, which was born as a man from her. Therefore, Mary is “truly the Mother of God”, as we sing in the hymn Axion Estin (It is truly meet).

Christ performed miracles on account of his divine nature, and hungered, thirsted and died on account of his human nature, but the person acting — the person (the hypostasis) doing and experiencing those things — was always the same.

In this way, the solution to all of these theological problems was this idea of the hypostatic union. The two natures are truly united, but not at the level of nature; rather, they are united at the level of hypostasis, in the one Person of the Incarnate Word of God. And in this way, the two natures simultaneously remain intact and unchanged.

And this is where we also see the importance of the icons. In the Old Testament, the depiction of the invisible God was forbidden. This commandment didn’t change, but instead, when God became man, he also became visible, and therefore depictable. Therefore, the depiction of Christ became not only something possible and permissible, but a necessary confession of faith.

Again, it is not abstract essences and natures which are depicted on icons, but persons (hypostases). Therefore, despite the fact that only the human aspect of Christ is visible, what we see depicted on an icon is the entire hypostasis of Christ, which includes both his human and his divine natures. Thus, the Christology expressed through iconography excludes the heresies of both Nestorianism and of Monophysitism.

And it is only with this beautiful balance between true union of the natures, on the one hand, and these natures remaining intact, on the other, that salvation becomes possible. In other words, it’s only in this way that the Saints are able to take up their places in the kingdom and for their images to adorn the walls of our temples alongside those of the powers of heaven. Amen.

Fr Kristian Akselberg